[Thomas Ashby]

When describing the causes of the first Anglo-Dutch war (1652-1654) in his Behemoth, or The Long Parliament (1681), Thomas Hobbes spoke of how directly preceding the conflict the English had ‘demanded amends for the old (but neuer to be forgotten) businesse of Amboyna’ among the points of friction, including trade and fishing, that ensured ‘the Warre was already certaine’ [1].

The centrality of ‘the affair of Amboina’– or ‘l’affare di Amboina’ – to the hostile relationship and threat of war between the Commonwealth of England and the United Provinces is also underscored repeatedly in the avvisi of Amerigo Salvetti, the Tuscan resident in London, across 1651 and 1652.[2] Hobbes and Salvetti are both referencing the infamous events that occurred across February and March 1623 in the Dutch colony of Amboyna, modern day Ambon in the Maluku Islands, Indonesia.

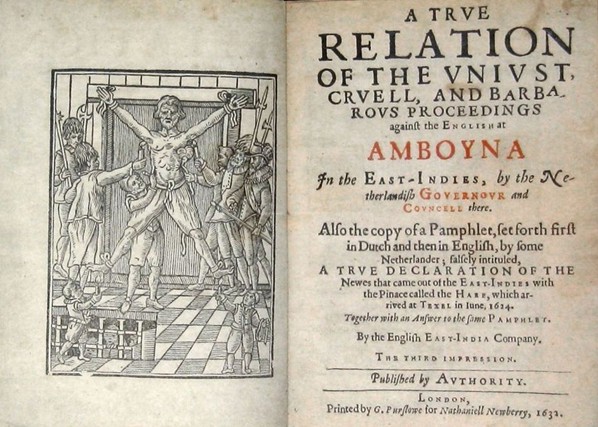

In late February 1623 a Japanese mercenary, Shichizō, began asking questions about the Dutch-held fortifications on Amboyna. Suspecting a conspiracy to seize the fort, the local authorities of the Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC) questioned and tortured the group of twelve Japanese mercenaries and an Indo-Portuguese slave overseer as well as the members of the small English East India Company (EIC) factory on the spice-rich island, totalling eighteen employees, who they suspected of orchestrating the alleged plot. In early March, following a series of extracted confessions and an impromptu VOC tribunal, nine of the Japanese mercenaries, the Indo-Portuguese overseer, and ten of the EIC employees, mostly English, were executed in a space outside the fort. The blood of twenty men drenched the ground and the heads of four men – Shichizō, two other Japanese mercenaries, and Gabriel Towerson, the chief agent of the EIC factory – were placed on pikes. The testimonies of the surviving EIC members became essential to the narrative of the ‘Amboyna massacre’ relayed by the EIC and its allies in the decades that followed.

It is this image of a brutal massacre in the aftermath of the Amboyna trial – by the early 1650s a widespread English grievance against the Dutch – that Salvetti references himself when he tells of the English demands for reparations in his avvisi across 1651 and 1652. Indeed, when Salvetti wrote about ‘the affair of Amboina’ on 2 February 1652 he does so describing the barbarity of the Dutch:

| “…this side [England] will demand untold sums for several accounts, and // in particular for the Amboina affair in the East Indies, where many years ago the Dutch treated the English with barbarous cruelty”. | “… verrà preteso da questa parte somme indicibili, per più conti, et // imparticolare per l’affare di Amboina nell’Indie Orientali, dove molti anni sono li olandesi trattorno l’inglesi con barbara crudeltà”. |

This is not, however, the first mention of the Amboyna trial in Salvetti’s avvisi of the 1650s. Moreover, it should not be forgotten that Salvetti was Florentine resident in London from 1618 and thus would have experienced and almost certainly reported upon the aftermath of the trial in England and witnessed the growing demand for reprisal and reparations across the last three decades.

Salvetti had mentioned the ‘tanta crudeltà’, ‘great cruelty’, associated with the Dutch at ‘la piazza di Amboyna’, ‘the square of Amboyna’, in an avviso on 6 October 1651, where he emphasised the rising demand for reparations from the EIC and its allies in the Commonwealth government:

| “… this [English] Company of the East Indies is beginning to revive against them the old quarrel of compensation for the great damage they received from them in those parts when with so much cruelty they [the Dutch] took them from the castle of Amboyna and everything inside it, and martyred many of their agents. The sum that they claim as compensation for their damages exceeds one million scudi, which, if it is not rectified in some way, could lead to ill will with that nation and even to an eruption of force; and we can already see that the mood of the nation [England] has grown much stronger against that nation [the United Provinces]”. | “… questa Compagnia dell’Indie Orientali comincia a rinovare contro di loro la vecchia querella di risarcimento de’ gran danni che ricevettero da loro in quelle parti quando con tanta crudeltà li tolsero la piazza di Amboyna con quanto ci havevono, et li martirizzorno molti de’ loro fattori. La somma che pretendono per risarcimento de’ lor danni passa un miglione di scudi, il che se non viene in qualche modo aggiustato potrebbe causare mala intelligenza con quella nazione et forze anche rottura; et di già si veggono qui gli umori di questa nazione molto ingrossati verso di quella.” |

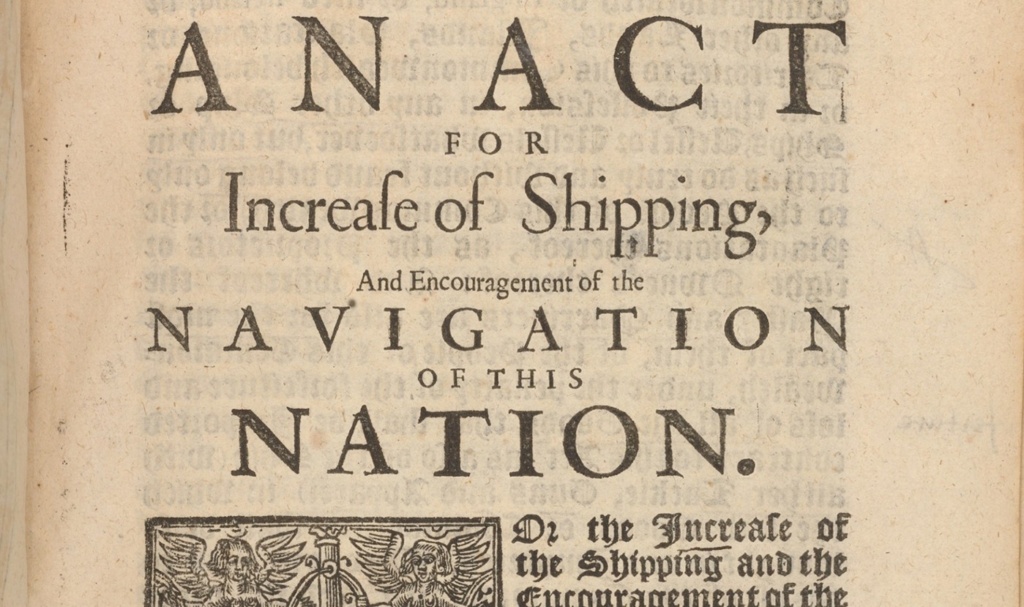

The following week, on 13 October 1651, shortly after the English had approved the Navigation Act, legislation fundamentally hostile to Dutch trade, Salvetti repeats this analysis, underscoring the threat of war between the two republics if the Dutch do not agree to settle English grievances.

By spring of the following year negotiations between the English and Dutch remained fraught and the point of Amboyna remained unresolved. Salvetti wrote on 12 April 1652 again, how:

| “… and they [the Dutch] will perhaps be forced to disburse some good sum of money to appease the [English] Company of East India, which is claiming millions of scudi as compensation for damages received by them many years ago in Amboyna in the said Indies”. | “…et oltre di questo saranno ancora forse forzati di sborsare qualche buona somma di denari per quietare questa Compagnia delle Indie Orientali, la quale pretende millioni di scudi per risarcimento di danni riceuti da loro molti anni sono a Amboyna nelle dette Indie”. |

Salvetti’s subsequent avviso, on 17 April 1652, accentuates the fundamental importance of the demanded Amboyna reparations to the English if the Dutch wish to avoid war:

| “… such as not being able to import into this kingdom [England] any merchandise that is not of their own country, the limitation of their fishing in these [English] seas, and the disbursement of some considerable sums of money to these merchants of the East India Company for damages received by them, many years ago, in those parts. These are the three most essential points that are disputed today” | “… come sarà principalmente quello del non potere importare in questo regno nessuna mercanzia che non sia del proprio paese, la limitiatione della loro pesca in questi mari, et lo sborso di qualche considerabile somma di denaro a questi mercanti della Compagnia delle Indie Orientali per danni riceuti da loro, molti anni sono, in quelle parti. Questi sono i tre punti più essenziali che hoggi si disputano…”. |

Incidentally, these three points listed by Salvetti are the same three terms, unagreeable for the Dutch, that are listed by Hobbes as the rationale for the war that would commence in the summer.

The English emerged victorious in the first Anglo-Dutch war and the English government, now a Protectorate, would in fact impose and secure reparations from the VOC in the Treaty of Westminster, agreed in April 1654. Alongside providing updates on the progress of negotiations, Salvetti also reported on the final ratification and articles of the treaty in May 1654.

Bibliography

A TRUE RELATION OF THE UNJUST, CRUEL AND BARBAROUS PROCEEDINGS against the ENGLISH at AMBOYNA In the East-Indies, by the Netherlandish GOVERNOUR & COUNCIL there. Also the Copie of a Pamphlet of the Dutch in Defence of the Action. With Remarks upon the whole matter. Published by Authoritie. Also the copie of a Pamphlet, set forth first in Dutch and then in English, by some Neatherlander; falsely entituled, A TRUE DECLARATION OF THE Newes that came out of the East-Indies, with the Pinace called the Hare, which arrived at Texel in June, 1624. Together with an Answer to the same Pamphlet. By the English East-India Companie (London: H. Lownes for Nathanael Newberry, 1624 [second impression].

ARTICLES OF Peace, Union and Confederation, Concluded and Agreed between his Highness OLIVER Lord PROTECTOR Of the Common-wealth of ENGLAND, SCOTLAND & IRELAND, and the Dominions thereto belonging. And the Lords the STATES GENERAL of the United Provinces of the NETHERLANDS. In a Treaty at Westminster bearing date the fift of April Old Style, in the year of our Lord God 1654 (London: William du-Gard and Henry Hills, Printers to His Highness the Lord Protector, 1654)

Clulow, Adam, Amboina, 1623: Fear and Conspiracy on the Edge of Empire (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019).

Games, Alison, Inventing the English Massacre: Amboyna in History and Memory (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020).

Koekkoek, René, ‘Rethinking the History of Reparations for Historical Injustices: An Early Modern Perspective’, Journal of Modern History, 96:2 (2024), pp. 253-290.

Milton, Anthony, ‘Marketing a Massacre: Amboyna, the East India Company, and the Public Sphere in Early Stuart England’, in The Politics of the Public Sphere in Early Modern England, ed. Peter Lake and Steve Pincus (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2007), pp. 168–90.

Pincus, Steve C. A., Protestantism and Patriotism: Ideologies and the Making of English Foreign Policy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996).

Venning, Timony, Cromwellian Foreign Policy (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1995).

Villani, Stefano, ‘Alessandro Antelminelli [alias Amergio Salvetti]’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004), Vol. 2, pp. 285-286.

Villani, Stefano, ‘Per la progettata edizione della corrispondenza dei rappresentanti toscani a Londra: Amerigo Salvetti e Giovanni Salvetti Antelminelli durante il Commonwealth e il Protettorato (1649-1660)’, Archivio Storico Italiano, 162:1 (2004), pp. 109-125.

Worden, Blair, The Rump Parliament (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1974).

Woolrych, Austin, Britain in Revolution, 1625-1660 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002).